To describe what it can be like to write a novel, I’ll offer a bit of my own experience: My first published novel, which began almost thirty years ago with a grudge. You would be amazed by how many novels are inspired by complaint; the advice “start small” has many applications.

I had written another first novel that had been rejected everywhere, usually with polite notes from editors that said something like, “Nice writing, but nothing happens.” One summer afternoon I was sitting on my porch, brooding over these rejections, at the same time watching my neighbor mow his lawn with a push mower, wondering why he bothered to wear his toupee while mowing his lawn on such a hot day, and feeling irritated by his push mower, which was making a pointed clattering noise, as if in rebuke to my own unmown lawn.

And in the same slightly spiteful vein, I thought: All these editors want something to “happen”? All right, I’ll give them something. I’ll give them a murder. That afternoon I wrote what became the first chapter of my novel A Crime in the Neighborhood, which is indeed about a murder, but it’s also about someone watching her neighbor and speculating uncharitably about him.

The murder itself was more or less written that day on my porch. But it took a long time for me to figure out that the opening crime was not actually the novel’s focus—in fact, I decided not to solve it. The effort to solve the crime was what I became more interested in, and what that effort did to the people involved. I wrote draft after draft, trying to locate the right point of view and to figure out the sequence of events.

Finally I gave it to a friend to read, who after several weeks remarked, ominously, “I’m almost done with it.” More drafts. Then I had a baby, and that of course took up some time, and then, when I finally did finish the novel, no one wanted to publish it. After I got fifteen rejections, one editor wrote to me and said that she liked the book until page 168 but following that I missed the mark. However, she said, if I would be open to discussing the book after page 168, she would talk to me about it. So I wrote another draft, had another baby, and that, at last, was that.

Writing a novel is often a long, crude, insecure business with a dubious outcome.I mention all this to explode the still-popular image of the austere novelist in a remote cabin with only a bottle of Jack Daniels and perhaps the Bible for company, who emerges after a few months with a completed manuscript of stern and lyric beauty. The truth is that writing a novel is often a long, crude, insecure business with a dubious outcome. You can spend years and years not sure of what you’re doing, writing something that in the end may not be great, and that perhaps no one will read. No one may read it even if it is great. I was once shown what was called “the morgue” at the office of the New York Times Book Review, a canvas dumpster on wheels filled with review copies of books that weren’t going to be reviewed. A sight once seen that can never be unseen.

So for God’s sake, why do it? Why spend years writing a novel, especially if you have no idea of what will become of it?

One answer is that this lengthy, ambiguous, ungainly period, if you can stand it, allows for something rare these days: the suspension of judgment. Room for indecision. Even for disorientation. Not the kind of disorientation that makes you disbelieve what’s right in front of you—a favorite tactic of certain politicians—but the kind that makes you suspect it may take a while to understand what is right in front of you. For help with clarifying this vital distinction, I will turn to Margaret Atwood’s Negotiating with the Dead: A Writer on Writing.

In her introduction, Atwood reveals that she polled a number of novelists with a question: What did it feel like, she asked, when they “went into a novel?” Not began writing a novel, but “went into” one—a question that already hints at the answers. Some of which were: “like groping through a tunnel,” “like being under water,” “like rearranging furniture in the dark,” “like sitting in an empty theater before a play or film has started, waiting for the characters to appear.”

What Atwood concluded from the responses she received was that going into a novel required confusion. Novelists confronted “obstruction, obscurity, emptiness, disorientation, twilight, black out, often combined with a struggle or path or a journey, an inability to see one’s way forward, but a feeling that there was the way forward, and that the act of going forward would eventually bring about the conditions for vision.”

Every writer has the experience of heading voluntarily into darkness, hoping for “the conditions for vision.” Hoping, as Atwood goes on to say, “to bring something back out to the light.” Every poem, essay, short story is an opportunity for illumination. What’s particular to novels is that the darkness is so prolonged. For readers, as well as for writers. Two or three hundred pages give you a lot of time to let your eyes adjust. But that is exactly what happens. As you go forward in a novel, your perceptions keep changing about characters and situations that in the beginning you probably thought you understood—because the characters probably began more or less as types, and their situations probably seemed more or less familiar. Yet as the characters become more complicated, their situations are also defamiliarized, and you can no longer predict how you will feel about them.

Usually, this defamiliarizing process requires a lot of stumbling and searching, chiefly by asking a series of questions that lead mostly to other questions. Writing a novel offers an extended experience of not getting to the point. So does reading one.

*

“Digressions are the very sunshine of the novel,” wrote Laurence Sterne back in the 18th century. A reminder that the novel has always been, by virtue of its length alone, anti-expedient. A novel meanders, pauses, stares into shop windows. Musings on agrarian reform appear in the midst of a love scene or metaphysical ponderings during a tennis lesson. And you don’t have to be Tolstoy or David Foster Wallace to claim the right to digress. Even the creator of Inspector Maigret, Georges Simenon, who published literally hundreds of novels, and wrote most of them in an eleven-day sprint, a novelist in an obliterating hurry whose novel spines are the width of asparagus stalks—even he stops to write passages like this one:

The train was in the station at Poitiers when the lamps suddenly lit up all along the platforms, though it was not yet dark. It was only later, while they were crossing some pastureland, that they watched night fall and the windows of the isolated farms begin to shine like stars.

Then, abruptly, a few kilometers from La Rochelle, a light fog came up, not from the countryside but from the sea, and mixed with the darkness. A lighthouse appeared for a moment in the distance.

Simenon could have written, “Inspector Maigret took the evening train from Poitiers to La Rochelle.” But he wants to capture that liminal moment when lights come on though it’s not entirely dark, and then the feeling of traveling from one kind of darkness into another, from that evening train platform into the night countryside with its occasional lit windows, and finally into a marine darkness, where light appears only in flashes. He wants to create atmosphere, which novels need to do as they move you through shades of perception and stages of comprehension, as well as through complications in the plot. He wants to give you time to adjust your eyes.

As you go forward in a novel, your perceptions keep changing about characters and situations that in the beginning you probably thought you understood.I’m not encouraging digression for the sake of digression, of course, but I would like to define digressions as where the writer changes the lighting. And I’d like to use the term expansively enough to cover everything from what critic James Wood calls the “descriptive pause” to the extended passages in a novel such as Middlemarch, where George Eliot stops the action to explain that provincial village’s attitudes toward politics, science, education, religion and the appropriate sphere for women.

In both cases the digression shades your understanding of the characters and their situations. Thus, while you’re waiting to see when idealistic young Dorothea Brooke will realize her mistake in marrying the heart-shriveling Mr. Casaubon, you discover the forces acting on her, why she thought that incarcerating decision was a bid for freedom, which makes it all the more painful to follow the consequences.

Digressions in a novel enlarge its capacity to affect you. They expand your responsiveness. You are being asked to stop, to attend, to hold a more elaborate idea of a setting, situation or character than you anticipated holding. Digressions are, in fact, experiences of capacity.

*

In his famous essay “Art as Technique,” written in 1917, the Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky argues that human beings are becoming so accustomed to thinking in abbreviated ways that we are in danger of abbreviating ourselves out of conscious existence. We tend to substitute automatic perception—“what a tall mountain,” “the sunset is beautiful”—for actually looking at whatever is in front of us. We see a general shape, not specific definition.

Shklovsky calls this general way of seeing the “‘algebraic’ method of thought” in which “things are replaced by symbols.” And I do not have to say the word “emoticon” here—though I just did—to indicate how much more “algebraic” our thinking has become since 1917.

The way to counter abbreviated, habitual ways of thinking, says Shklovsky, is art. Because art prolongs perception. “The purpose of art,” he writes, “is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.”

The avatar of prolonged aesthetic perception is the novel. In his introduction to The Portrait of a Lady, Henry James writes, “The novel is of its very nature an ‘ado,’ an ado about something, and the larger the form it takes, the greater of course the ado.”

To make an ado means to take something apparently small and magnify it, to demand our attention for something we may not have, previously, considered worth it. In the opening of her novel Sula, Toni Morrison wants to make an ado about a vanished Black neighborhood.

In that place, where they tore the nightshade and blackberry patches from their roots to make room for the Medallion City Golf Course, there was once a neighborhood. It stood in the hills above the valley town of Medallion and spread all the way to the river. It is called the suburbs now, but when black people lived there it was called the Bottom. One road, shaded by beeches, oaks, maples and chestnuts, connected it to the valley. The beeches are gone now, and so are the pear trees where children sat and yelled down through the blossoms to passersby. Generous funds have been allotted to level the stripped and faded buildings that clutter the road up to the golf course. They are going to raze the Time and a Half Pool Hall, where feet in long tan shoes once pointed down from chair rungs. A steel ball will knock to dust Irene’s Palace of Cosmetology, where women used to lean their heads back on sink trays and doze while Irene lathered Nu Nile into their hair. Men in khaki work clothes will pry loose the slats of Reba’s Grill, where the owner cooked in her hat because she couldn’t remember the ingredients without it.

There are many wonderful aspects to this paragraph, but perhaps the most astonishing is Morrison’s simultaneous erasure and creation of the Bottom. Again, this is the novel’s opening paragraph, so our immediate understanding is that this neighborhood has vanished—it’s stated in the first sentence: “there was once a neighborhood.”

Yet at the same time, Morrison prevents us from “getting” this fact, even as she asserts it. She starts by presenting us with a vivid absence: “the nightshade and blackberry patches” torn from their roots to make way for the Medallion City Golf Course. Then she layers that absence: “The beeches are gone now,” and the pear trees, and also the children who used to yell from the branches. Except now we see those trees, those children, as if they still exist.

Writing a novel offers an extended experience of not getting to the point. So does reading one.All that’s left of the Bottom, Morrison tells us next, are some “stripped and faded buildings that clutter the road up to the golf course.” Yet here she intensifies her layering of this world even as she continues to insist that it’s gone. She does so by colliding future and past, telling us first that the Time and a Half Pool Hall is going to be razed and then giving us those long tan shoes that once pointed down from chair rungs. We see the steel ball that will knock down Irene’s Palace of Cosmetology and then those heads Irene lathered in sink trays.

We are asked to hold contradictory visions, to see something destroyed and complete at the same moment, an extraordinarily dynamic, complex demand on our perceptions. Our emotional response comes from watching the intense particularity of this neighborhood erased seemingly right before our eyes, even though it’s already gone. And even though we’ve only just encountered it.

In Portrait of a Lady, James wants to make an ado about Isabel Archer, an ardent, free-spirited young woman, a recent heiress, who hopes for an independent future, and briefly seems poised to achieve something like it, until she is cannibalized by cynical sophisticates after her money. One technique for making an ado is to present us with a given—a once vibrant neighborhood will disappear, a naive young woman will be betrayed—and then find ways to make us hope against that given. You can, of course, do this in shorter forms as well; Frank O’Connor does it powerfully in “Guests of the Nation,” a story that illustrates what Edward P. Jones calls “monstrous inevitability.” But in novels, that experience of hoping against reason, of hoping against inevitabilities—a complicated and profoundly absorbing act of sympathy—is elongated.

Subplots are another technique for making an ado, and again you certainly find them in shorter forms, such as the braided essay, but they are critical in novels. Subplots layer your impression of a subject by offering up concurrent narratives related to it. In Sula, for instance, we follow four or five main characters, mothers and daughters, all residents of the Bottom whose fates are entwined. Subplots not only draw your attention to the multiplicity of experience—the opposite of flatness—they remind you of the many contingencies of your own life. No one has “one” life, in other words: we are all made up of subplots: jobs, families, communities; we feature in the subplots of other people’s lives, as other people feature in our own.

*

What is worth an ado? I suppose every writer faces that question; but for novelists, with perhaps years of work stretching ahead, it’s particularly pressing. Of course, anything on earth is worth an ado, if you can figure out why. And that “why,” I think, comes back to capacity. What can your subject hold? Not what does it hold, what can it hold? For you and for your readers?

In response to that question, here’s another example of a novelistic “ado.”

When Virginia Woolf began writing Mrs. Dalloway she was revisiting a minor character from an earlier novel, The Voyage Out, where “Mrs. Dalloway” was a superficial socialite. This was a type Woolf was fond of deploring, and in her subsequent novel she originally meant to satirize Mrs. Dalloway as a social hostess who plans to give a party and then commits suicide at the end of it.

Yet though the novel’s structure remains narrowly focused—opening on the morning of Mrs. Dalloway’s party and concluding that evening—the story itself expands exuberantly until it becomes all but uncontainable. Starting with the first pages, as Mrs. Dalloway sets out to buy flowers on Bond Street and responds intensely to whatever she encounters:

in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages and motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment of June.

Mrs. Dalloway is a human digression—everything interests her. And in her enjoyment of that June day, her appreciation of a single moment’s many registers, from the “bellow and uproar” of the street to an airplane’s “strange high singing,” she quickly transcends Woolf’s early idea of her as a social butterfly and becomes almost goddess-like in her immersive interest in life around her. Her pleasure in that June moment is itself an ado, one that transforms street noise into opera and an airplane into a soprano. Critic Phyllis Rose calls Mrs. Dalloway “perhaps the most buoyant novel ever written.”

No one has “one” life, in other words: we are all made up of subplots.Not that terrible things don’t happen. There is still a suicide. There is hurt, harm, mental illness, suffering. The First World War has only just ended. Life in London a century ago was no more fair or forgiving than life in London today. But as Rose points out, what this novel offers in reply “to the decay of the spirit, the deaths it variously records, is an intense response to the moment.”

An intense response to the moment. Poetic territory. What can the novel add to what is done more penetratingly and certainly more economically in poetry?

Perhaps it’s the normalizing of heightened responsiveness, making what would be extraordinary moments of clarity in “real” life seem continual, almost ordinary. The novel’s hallmark is an illusion of dailiness, but a dailiness embedded with small revelations, discoveries and visions, all attributed to characters with whom you come to identify. Each chapter contains a slow drip of intense responses that sustain your sympathies with those characters while progressively complicating them. And again, this happens for both writer and reader.

For instance, Woolf’s idea of a “hostess” itself became transfigured by Mrs. Dalloway, shifting from dismissal to identification. While she was working on that novel, Woolf noted in her diary: “One writes to bridge over the abyss between the writer and the reader, or between the hostess and the unknown guest.”

I love this way of thinking of readers, not as people who must be captured, appealed to or seduced, but as “unknown guests,” a relationship that makes sense to me, perhaps because the questions of responsibility are so clear. How do you greet your readers and invite them in? What will make them feel comfortable enough to stay? Especially if you are hosting them for hundreds of pages, what kind of sustenance and entertainment are you offering? Once a guest is under your roof, the ancient laws of hospitality require you to take care of them—ignoring those laws is perilous. (If you don’t believe me, look at what happens in Macbeth.)

Which doesn’t mean that you can’t lead your guests on a tour of the dungeons, switch out the lights and chain them to the wall—if the story requires it—only that you must lead them back out again, and perhaps offer them an aspirin and a glass of water. The reader, the “unknown guest,” requires your care. And the experience of being cared for, held by a well-told story, can be transformative, too.

*

Along with the rewards of not getting to the point, prolonged darkness, making a fuss over small things, and spending a lot of time with unknown guests, I’d like to offer yet another reason for writing and reading novels: privacy.

Privacy, like the suspension of judgment, is increasingly hard to find in these days of internet tracking, surveillance, and data harvesting. For readers, a novel is a lengthy plunge into invisibility. Alongside your visible life among co-workers, family, friends, you are also living—sometimes for weeks—with people and places no one else knows. Even that novel’s other readers will not picture its people and places, its scenes, as you do, unless the novel gets made into a movie. But while engrossed in reading a novel you are conducting a dual life, a hidden life, and in that “other” life you are immune from influencers, advertisers, algorithms, clickbait, dark posts, followers. You have no digital exhaust. No one can trace you.

For writers, a novel offers the same privacy, plus something else: a protracted period of deep, necessary concealment while you blunder along in a made-up world, knowing that no one will see what you’re doing, or care, quite possibly for years. You can get it wrong again and again.

For example, in my own first published novel I wrote several drafts from a mother’s point of view, only to realize after hundreds of pages that I had chosen the wrong character to tell the story, that it was her daughter who should tell it, but in retrospect. It was a realization that made all the difference; and yet, I would not have understood the mother’s character nearly as well had I not spent all that time in her head. Choosing the wrong point of view can be a valuable mistake. With the novel I just finished, I began with a first-person narrator only to realize after, again, hundreds of pages, that the story should be in third person. And then, after many more pages, I realized I needed three perspectives, including that of a character who started out as dead.

The experience of being cared for, held by a well-told story, can be transformative, too.Was this all wasted work? Yes, if I were trying to write a novel in eleven days. But if I measure my novel’s value partly by its density, by the experience that has gone into it—the thousands of questions I have asked myself, the choices I have weighed, my attempts to do not the obvious thing but the more interesting one—then all that work has been worth it. Every character, description, conversation, action that I spent time writing and then deleted has added to the story. I sometimes think of my novels as built atop a graveyard of ideas, yet that is richly occupied soil.

As Henry James notes, in Yoda-like fashion, “Strangely fertilizing, in the long run, does a wasted effort of attention often prove. It all depends on how the attention as been cheated, has been squandered.”

*

Amid all this useful squandering, however, my goal as a novelist is still to have readers. And so I go along, typing and typing, trying to find the right perspective, creating my characters and figuring out their problems—occasionally committing a murder just to keep things moving—getting closer and closer to knowing what they want and what they’re afraid of. So that by the final drafts when my characters ask What am I supposed to do here? I have a coherent response. I’ve thought about them for so long that I usually know not only what they need to do, but how and why.

A character in a novel is real, E.M. Forster writes in Aspects of the Novel, “when the novelist knows everything about it. He may not choose to tell us all he knows—many of the facts, even of the kind we call obvious, may be hidden. But he will give us the feeling that though the character has not been explained, it is explicable, and we get from this a reality of a kind we can never get in real life.”

Ironically, to make a character feel “explicable,” the novelist has to find ways to keep readers wondering about them. Unlike actual human beings, a character is limitable, but novels have room for a lot of emotional cross-hatching, for deepening characters’ contradictions and seeding new mysteries, for surprising us with gestures we had not thought a character capable of making, and yet looking back we realize those gestures had been promised from the start—all so that we’ll agree to spend hours pondering a few invented people and their troubles.

Rarely are we as absorbed in wondering about our friends as we are in wondering about characters in a novel, even though, in the end, characters have no secrets, and our friends have so many. In this way, novels again challenge our capacity by offering extended, focused, and sometimes deeply moving experiences of wondering about other people. People you might otherwise never know, or want to know, and yet as Forster suggests, you’ve been made to feel that you do know them.

*

But once more back to me, the novelist at her desk, typing and typing, trying to propel my characters forward, worrying about engaging my readers, hoping to reach the end of the story before I die—and all the while something else looms closer and closer. A question that novelists can avoid longer than most: What am I trying to say?

Such a reasonable question. If you are going to write something hundreds of pages long, shouldn’t you be able to say why you wrote it? Yet, after decades of novel writing, I have come to believe it’s the wrong question. “What am I trying to say?” is the expedient question, the getting-to-the-point question, the here’s-my-advice question. It is not a capacious question. Especially if it strides straight to an answer.

A more capacious question might be “What am I making an ado about?” A question that at least reliably leads to more questions, and away from recommendations and pronouncements. In an 1888 letter to his editor, Anton Chekhov points out, “You are right in demanding that an artist approach his work consciously, but you are confusing two concepts: the solution of the problem and the correct formulation of the problem. Only the second is required of the artist.”

An idea taken up by James Baldwin in his essay “The Creative Process”: “A society,” he writes, “must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven. One cannot possibly build a school, teach a child, or drive a car without taking some things for granted. The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.”

As an example of Baldwin’s prescription to drive to the heart of an answer and expose the question it hides, consider Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels, sixteen hundred pages centered on the friendship between Lila and Lenu. An ado if there ever was one, which begins when they are little girls in Naples in the 1950s and covers forty years. Chapter 1 of Book One, My Brilliant Friend, starts like this: “My friendship with Lila began the day we decided to go up the dark stairs that led, step after step, flight after flight, to the door of Don Achille’s apartment.”

Novels are long roads full of switchbacks and roundabouts. And they rarely take you where you thought you were going.A marvelously intriguing first line that seems like the beginning of a good, stable answer: Friendship is important. Hang onto your childhood friends, especially if you’re going somewhere dark and mysterious. But as anyone who has read those books will tell you, they chronicle hundreds of temblors in the lives of Lila and Lenu—including long separations, betrayals, periods of great hostility, reunions, more betrayals, rescues, disappearances. And yet there remains a deeply complicated attachment to each other and where they came from. At least on the part of the narrator, Lenu, who never stops wondering about her brilliant, difficult friend.

Therefore, a question hidden by the answer “Friendship is important” might be: What binds one person to another? Is it ever possible to know?

Though if Chekhov were to take over here, the question might become: How can we tolerate even a single other human being, when human beings cause one another such suffering and confusion? But we must love each other! But how, but how?

No two readers will frame a novel’s questions in the same way.

*

Like the novel itself, this essay has digressed. I set out to describe what it can be like to write a novel and why I think it’s worth all the work and uncertainty, and the same with reading them. Somehow I wound up wondering how we can all tolerate each other. So I will close by saying that I believe in the capacity of the novel, in its formal demonstration of the possibility for greater insight and compassion over time. I believe in the prolonged imaginative privacy a novel affords. I believe in its power to disrupt inevitabilities. I believe in its inconvenience. Especially now, when so much information is continually coming at us, so fast, from all directions, it’s hard to know what to pay attention to, what to trust—and anyway, who has time to decide? Something else is always trending.

“When information is cheap,” notes science historian James Gleick, “attention becomes expensive.”

Writing and reading novels are major investments of time. Novels are long roads full of switchbacks and roundabouts. And they rarely take you where you thought you were going. But the return on that investment is an excursion through a wide landscape of passing joy, hilarity, sorrow, doubt, generosity, cruelty, shocks of beauty, shocks of horror, shocks of love. Above all, the shock of how profoundly things can change. Though novels deal less with shock, I have found, than with a slow, sustaining electrification.

__________________________________

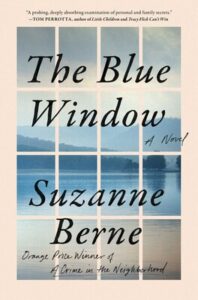

The Blue Window by Suzanne Berne is available from Scribner/Marysue Rucci Books, a division of Simon & Schuster.

https://ift.tt/aNZ6tPj

2023-01-10 09:59:55Z

CBMiWGh0dHBzOi8vbGl0aHViLmNvbS9zdXphbm5lLWJlcm5lLWFza3MtdXMtd2h5LXdyaXRlLWEtbm92ZWwtd2h5LXJlYWQtYS1ub3ZlbC1hbmQtd2h5LW5vdy_SAQA

0 Commentaires