I’ve never been good at writing titles. They’re all too factual, and usually too boring. The titles I considered writing here were:

1) UCI Esports World Championship Qualifier Banned after Spicy Real-Time Manipulation of Data Stream

2) Zwift Race Cheating Gets Even More Covertly Brazen During UCI World Championship Qualifier

3) Previously Outlined Zwift Cheating Hack Actually Implemented in UCI eSports World Championships

All would work, and there are many more potential good ones! However, I don’t think any of those titles really capture just how ballsy this particular attack is, and more importantly, how big of a deal it is going forward to UCI’s Esports World Championship series. As for the titles, feel free to add your own in the comments section. The winner gets nothing.

So why am I writing about this? Well, I’ve long found these Zwift cheating bans interesting. To be clear, Zwift is only doing cheating bans on essentially pro-level races. Races where you’ve agreed to a set of terms, agreed to certain verification standards, etc… These aren’t being done on your run-of-the-mill DIRT events.

However, what fascinates me about them is just how increasingly technically brazen riders cheaters are getting with these. Mind you, these are only the ones where people have been caught and publicly flogged. In this case, arguably it’s the very brazenness of not just the tech, but the race finish usage of it, that outed him.

An Unbelievable Mountaintop Finish:

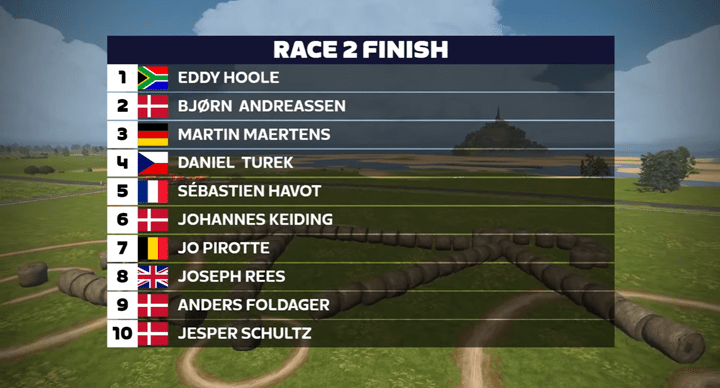

Back on November 13th, 2022, Zwift had a continental qualifier event for the upcoming UCI Cycling Esports World Championships. This particular race was for Europe & Africa, though of course, the World Championships cover, ya know, the world. That doesn’t occur till mid-February when everyone is solidly sick of trainers. That race even had a livestream of it, whereby 5,978 people watched the event unfold. This qualifier included 124 starters, with 50 of those advancing to the next race. Additionally, the winner got an automatic ticket to the world championships. Most notably, the livestream even had webcams from some riders – including the individual in question.

The 27.2km race of Roule Ma Poule had been progressing normally, but there was one final ~100m ascent for the last couple kilometers, with a hill-top finish. Two riders had broken away from the pack, while the main pack including our man in question Eddy Hoole, were back quite a ways.

It’s at that moment, right before the offending action occurred, one of the two announcers, Dave Towle, says (at 34:38), and I quote:

“I don’t know all 7 of the deadly sins, but I know two of them are greed and sloth. And certainly sloth is not the issue out here, but greed might be.”

Mere moments later at 37:28, rider Eddy Hoole starts a breakaway from the pack at the base of the final climb of the race – a daunting multi-minute climb to the finish. In doing so he’s holding 8 w/kg up this hill for some 4 minutes in duration. At times breaking over 10 w/kg, in the middle of this extended climb. You can listen to the announcers astounded as Eddy inexplicably closes the gap from the peloton to the two leaders, passing them as Nathan Guerra says he “comes flying back like they’re standing still”, ultimately taking the win and qualification spot:

Just after crossing the line (41:23), announcer Nathan Guerra says:

“He took on with an amazing effort, something we’ve almost never seen before”…“that is one of the best efforts, I literally have ever seen for a catch on Zwift, to go flying right on by, Eddy Hoole just did what I thought was absolutely impossible”.

Which, would turn out to be true. It wasn’t possible, and is largely beyond known human performance levels.

And again, just three minutes later when they cut to a side-by-side of the announcers, announcer Nathan re-iterated the implausible nature of it, and even seemed to be contemplating it, and seemed less excited and a bit more like the gears were already turning in his head. Follow that another 2 minutes later and announcer Dave Towle actually mentions the verification process ensuring that this data is valid from the trainers and power meters.

The Datastream Attack:

Yesterday, December 7th, 2022, Zwift published their so-called “Performance Verification Decision” document to their site. This document is basically the final list of charges and included ban for the rider. This doesn’t get published immediately after the event, but rather, this is the culmination of that process. The process includes bilateral communication with the rider, teams, etc… It’s aimed at figuring out whether cheating was purposeful, or perhaps accidental (such as a misconfiguration/miscalibration of a trainer/power meter). And in fact, it goes through those very steps here.

I think in the past, some of Zwift’s initial performance verification decisions were on shaky grounds (while others were very solid), however, they’ve gotten better over the last two years, and it seems the only cases making it to public view (and thus bans) are the most damning cases. Obviously, Zwift wants to limit its legal liability here.

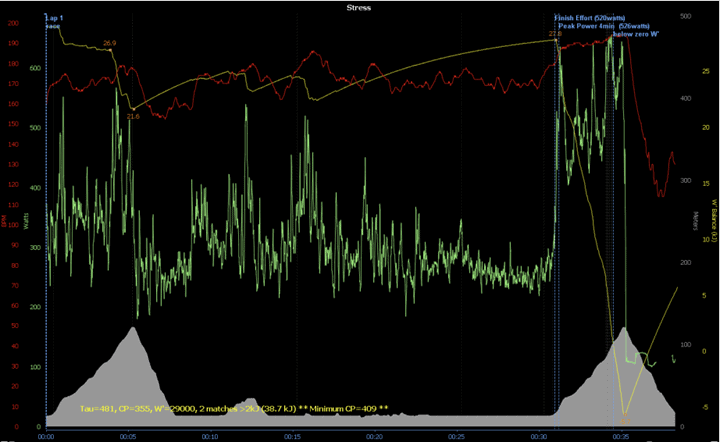

Here’s a chart of the entire race for the rider in question, Eddy Hoole:

The data sets are as follows:

• Terrain/Altitude – Grey

• Power – Green

• Estimated Energy Reserves – Yellow

• Heart Rate – Red

(In case you’re wondering, Estimated Energy Reserves is W’bal, which is a way of estimating potential wattage over time – roughly like MPA from Xert. Here’s a bit more detail on W’bal.)

The focus area here is on that final climb, basically where all that blue text is at the top, and where the power jumps up. It’s also the section I outlined earlier. The rider in question, according to Zwift, nailed the following wattages:

- Total effort = 4min 16sec @ 526 Watts average

- Best 4min average power = 526 Watts

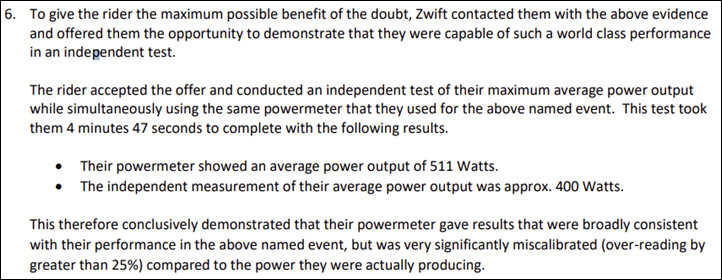

Zwift says that given the rider’s weight, this equates to a sustained output of 8.5W/kg, which in turn would require a VO2Max of 90. Zwift goes on to note that the highest-known Tour de France or Olympic Persuiters have a VO2Max of about 85. As usual, Zwift then gives the rider the opportunity to have an independent lab conduct a VO2Max test, which, the rider accepted. Here’s that excerpt:

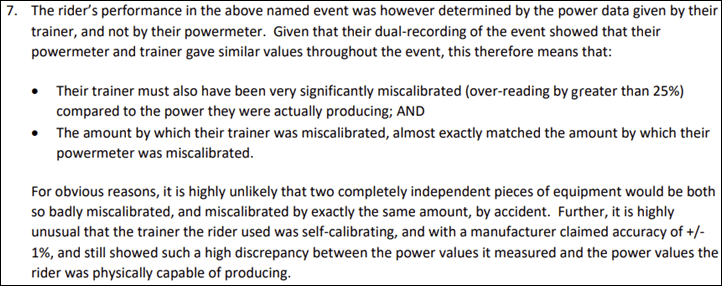

As you can see, at this point you’re thinking ‘Oh, just a miscalibrated power meter’. Except, remember that Zwift requires dual-recording for these races from both a power meter and a certified trainer. Now, Zwift (still, seriously, 3-4 years later), doesn’t dual-process this data in real-time as has been begged for, for years. Instead, its post-processed when required for stuff like this. So, what’d that data look like? Well, in short Zwift says the two were basically the same:

Even more, Zwift threw a bit of a knife-to-the-heart in there by noting that the trainer the rider was using is ‘self-calibrating’, which is basically a recent Wahoo KICKR or TACX NEO series device. I can’t quite tell from the webcam angle what he’s using.

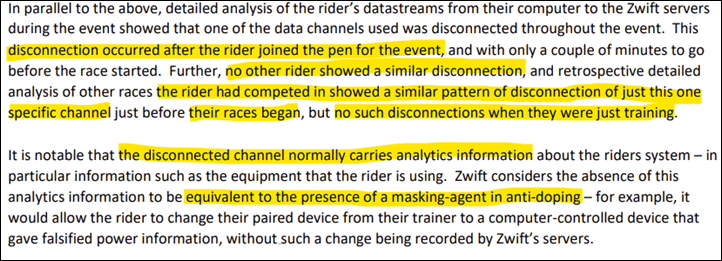

However, here’s where the spicy part finally comes in. Zwift noticed that after the rider joined the pen, there was a brief disconnection that occurred to Zwift’s servers. Interestingly, no other riders had this happen. Yet inversely, this rider had this happen in every race, but never any regular Zwift training rides. This particular data channel included analytics information about the sensor:

Note about Zwift says:

“Zwift considers the absence of this analytics information to be equivalent to the presence of a masking-agent in anti-doping – for example, it would allow the rider to change their paired device from their trainer to a computer-controlled device that gave falsified power information, without such a change being recorded by Zwift’s servers.”

In translation: The rider is inserting a device/software into the middle of the (basically open) data stream to dynamically change it, providing an offset (increased power), that gives the rider a boost.

When asked about this, the rider had no answer, but instead deleted 150 publicly visible dual-recordings from ZwiftPower (a website used for displaying these recordings post-race to prove your data). The rider has since deleted or made private all his social media accounts, including his Instagram account which listed him as a “Web Software Developer”.

Based on that, Zwift says they’re satisfied that the rider knowingly cheated, saying:

“The Performance Verification Board is comfortably satisfied that the power recorded by the trainer and used in-game did not match the actual power produced by the rider and/or was not the actual power measured by the trainer, and therefore that the rider’s performance in the event cannot be verified.

Further, the Board is comfortably satisfied that this was a result of deliberate manipulation of data, masked by the deliberate disconnection of the Zwift analytics datastream channel, rather than accidental miscalibration of two independent pieces of equipment by the same amount coupled with a coincidental accidental loss of analytics data.”

As a result, the rider received a 6-month ban, given it fell under a Tier 3 section – specifically, “Bringing the Sport into disrepute”. In case you’re wondering what else is in a Tier 3 ban, I asked Zwift:

Tier 3: Bringing the sport into disrepute

● Examples include, but are not limited to, the following:

– Fabrication or modification of any data

– Equipment modification or other external trainer control

– Use of bots / simulated riders

– Identity fraud

– Abuse of race officials● Sanctions include, but are not limited to, the following:

– First violation: Six month ban from Zwift Cycling Esports events.

– Second violation: One year ban from Zwift Cycling Esports events.

– Third violation: Lifetime ban from Zwift Cycling Esports events.

Finally, Zwift ended the performance decision with the usual taunt, saying, ‘if you can prove it, we’ll drop it’, which is basically a CYA in case the rider claims their first test was on a bad day.

“If, within 1 month of the issuing of this decision, the rider can perform an independent laboratory test & antidoping test to the satisfaction of Zwift that shows that they are naturally physiologically capable of producing the results they have recorded in this event (including, but not limited to, an average power output of 8.5 W/kg for 4 mins), the Board will happily reverse its decision, reinstate the rider’s results, and additionally reimburse the rider for the cost of the tests.”

Concurrently, the team he was riding for has terminated their relationship with him, as noted in a statement they published.

“On Saturday 3rd December 2022 Esports Team Toyota CRYO RDT terminated their relationship with rider Eddy Hoole. The team was requested not to make any public statement while a Zwift Accuracy and Data Analysis Group (ZADA) investigation was ongoing. The results of this investigation were released today Wednesday 7th December 2022….

…As can be seen from ZADA’s determination the nature of this case is such that the team would not have the means to suspect / identify / investigate circumstances such as these as they require access to Zwift Server log files and an in-depth knowledge of how to interpret these. However, it was clear to the Management Team that as a result of initial information received from ZADA without any plausible explanation from the rider there was only one decision open to us.

Esports requires a basis of trust on the part of all involved to ensure that the sport is fair, and we have and will continue to work with ZWIFT / ZADA in an effort to achieve this. We are saddened by this situation and will now study in detail ZADA’s report to establish any lessons which we can learn from it.”

However, while the story for the rider ends here, it doesn’t end here on the tech side.

Previously Demonstrated at Hacking Conference:

Now, the kicker about this whole thing is that this exact attack vector was previously shown at a security conference back in August 2019 by Brad Dixon and Mike Zusman, from a security consulting firm. However, prior to that on March 5th, 2019, Uncle Keith Wakeham demonstrated a very similar variant of this too (I say Uncle, because in the sports tech industry, everyone knows Keith and his Titan Labs, and almost all roads involving quirky data things and fun data projects, tend to lead back to Keith). When in doubt, Uncle Keith probably knows the answer, or why it exists. I actually wrote about both back in 2019.

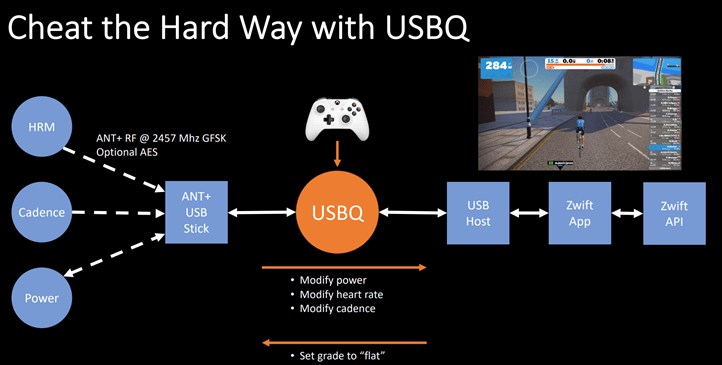

Both of these attacks essentially did the same thing – they were so-called ‘Man in the Middle’ attacks. Essentially, they took the data stream from your trainer or power meter (or heart rate, as also shown), and then tweaked the values before sending it onward. This is relatively easy to do over ANT+, but slightly more complicated over Bluetooth Smart (still, not impossible, just a bit messier).

In the case of the attack that Brad/Mike showed, it was a bit more simplistic in terms of how it added spice to your ride. It offered either a set multiplier for your power, or, it could just ride for your, and generate a fake HR number. However, the fake HR number wasn’t super believable given it was a bit more of a static value. It didn’t have the human nuance that would show like a human suffering with slight ups and downs. Same goes for power. However, the multiplier mode (called EPO mode in their presentation) would be believable, since it was using your real power as a baseline.

But it did show how they could execute it, on different channels and even controlling it via a game controller:

Meanwhile, Keith’s hack wasn’t re-transmitting things, but simply acting as the sole source of data. In other words, he could just sit there and do nothing and control a rider profile to whatever power/HR he wanted. In his case, he did add variability to the power/cadence/HR numbers so that it was believable (or at least, more believable).

Given in this case we saw the rider actually riding his bike via webcam, it’s unlikely that he was just using an Xbox controller as in Keith’s hack. However, that doesn’t mean aspects weren’t leveraged.

The implementation shown by the rider in question seems to be closest to what was demonstrated at the DefCon event. However, what’s interesting is the channel drop portion. Zwift isn’t clear in their document precisely what channel was dropped. However, given that Zwift notes *both* datasets transmitted/recorded for the race showed similar values, that tells you that this cheat was being applied to not just the trainer or power meter, but actually both of them.

That’s because if it applied to just one of them, it would have demonstrated a difference between the two required data sources. And notably, in this cheat, the rider was seemingly able to turn it on or off at will. Or, perhaps he just rode easy for the majority of the race with the multiplier always on.

Going Forward:

The challenge with this cheat is that it’s relatively hard to detect when used properly. In this case, the rider effed up by using it on a mountain-top finish with a crazy breakaway win. Had he stayed with the leaders and then just edged them out at the line, he’d probably never been flagged. Further complicating things is that he’d apparently been using the cheat for *all races*, effectively establishing a very good baseline that large data set algorithms might have ignored. Though, he screwed up by also not using it for training – which would have given him some plausibility excuse of a weird technical issue.

The mitigation for this type of attack is the same as it was in 2019 when I posted about: Encryption or digital signing at the trainer level, which ensures the data stream isn’t tampered with. In fact, Keith goes into detail on this in the second half of his video (there are YouTube chapters in it).

Of course, the challenge there is that getting the trainer industry to agree upon even the most basic of standards has been impossible in recent years. They can’t agree on how to implement steering, how are they going to agree to fundamentally change the direction of smart trainer protocols? All at a time when one trainer company is suing other trainer companies, and the remainder are closing their openness doors.

The problem is: The cat’s out of the bag. Sure, the idea was published years ago, but there wasn’t much proof anyone was using it. Now, not only are people using it, but someone that had won an automatic ticket to the UCI World Championships used it. And he would have used it successfully had he not been, to quote Dave Towle, “greedy”. And there’s no doubt he would have eventually used it in the actual UCI World Championships, likely to outright win.

It’s at this point that I remind you that the UCI has a person (division in fact), dedicated to esports racing and trying to establish believability in the sport. It’s a heck of a lot different when the UCI knocks on Zwift/Wahoo/Elite/Tacx/Saris/etc’s door and says they need to implement something, than if someone like me says it. But at this point, the presence of this cheat in the wild demonstrates that if the UCI wants this title to have any meaning at all, then they need to start demanding some changes.

With that – thanks for reading!

0 Commentaires