I used to think authors who spent twenty years writing a book must be sad, pathetic creatures. Now that I’ve become one, I see it’s far more complicated.

The first time I learned that someone I knew had taken twenty years to finish a book, I was in graduate school, in my late 20s. I remember holding her tome (a long biography) and doing the math. She’d averaged thirty pages a year. I thought to myself, “How totally pathetic.” Surely anyone who spent such a large chunk of a writing life on one book had proven part success and part failure? I congratulated her on the achievement, of course, but secretly, I felt sorry for her. I vowed I’d never make that wrong turn.

Yet I find myself, at age 55, having done almost exactly what I promised my younger self not to do. I’ve just published a biography of two nineteenth-century sister novelists I began researching in 2004. Now that I’m on the other side of that unintentionally long and winding author-road, I can report back that my feelings about having done it are largely positive, if also a little fraught. Taking stock of those mixed emotions has led me to want to share them, along with a few tips that helped me persist to completion. Even if you don’t ever find yourself in this boat as a writer, I hope you won’t make the mistake I once did of pitying those of us who have been.

I certainly didn’t begin this book by thinking, “Next I’m going to devote approximately two decades of my life to a biography that considers thousands of unpublished letters and dozens of novels by two dead women.” Few of us writers create work plans that can be measured in double-digit years. In fact, if I’d known at the beginning how drawn out a process this would become, I probably wouldn’t have started it. In hindsight, I’m glad, not sorry, that I didn’t know.

Surely anyone who spent such a large chunk of a writing life on one book had proven part success and part failure?At first, I thought I was writing just one book chapter about the older sister, Jane Porter—a pioneer in historical fiction who published a bestseller in her 20s—and I did that. But the Porter materials I’d gathered proved too powerful a draw to simply walk away from. I’d always loved reading biographies and intended to write one someday. There hadn’t been a published biography devoted to these once-celebrated and now-forgotten sister novelists, which seemed a travesty of literary history. It didn’t occur to me that perhaps so few had tried because there might be too much information—a sad rookie error.

Even as that realization sunk in, I felt called to unearth the stories of these sisters’ trailblazing lives and careers. I know it sounds a bit woo-woo, but that’s the feeling that drove me on. It must be common enough among those of us who choose long-term projects. At some point, we find we just can’t not. Two or three years after I began, a plan for a biography began to take shape. My devotion to Jane Austen—the Porter sisters’ exact contemporary—also spurred me on, because the Porters struck me as having lived funhouse-mirror versions of Austen’s famous fictional plots.

I figured I’d spend two or three years on this biography—four tops. I began to track down what ended up being more than 7,000 letters in archives across the globe. I was armed with the hopeful and perhaps naïve belief held by any writer who embarks on a big book—that others would eventually share my interest in, if not my obsession with, with the subject. I figured that if I couldn’t put down the Porter sisters’ unpublished letters, then others would be similarly captivated. That hope that drove me forward through starting to read and take notes on a massive number of manuscripts.

Writing a biography isn’t only time-consuming; it can also be notoriously expensive. I applied for travel grants and fellowships and became one of the lucky ones whose visits to archives were subsidized. As a professor, I took these trips mostly in the summer, when I wasn’t teaching, although a few research leaves allowed for travel during the semester, too. The emotional costs of going away from home became high as well, because by then I’d given birth to two children.

In 2008, I was awarded a grant to work at a far-away library that required researchers to be in residence for at least thirty consecutive days. I packed my bags and left our young sons in the care of their father. I worked maniacally in the archive, maximizing every moment. At the two-week mark, I came home for a long holiday weekend. When I went to pick up one son from preschool, his teacher pulled me aside in her classroom and said, “How could you do this to your child? How could you leave him like this?”

I cried. I doubted my choices, while recognizing that my husband never faced these questions when he left town. The teacher later apologized to me, but I can’t begin to calculate how that interaction affected me. I second-guessed myself as a parent anytime I prioritized writing time or research travel. Whenever I could, I took one child with me on these trips to archives, accompanied by my retired mother, who provided free childcare. I knew I was fortunate to have support of all kinds, but finishing thirty pages a year began to sound like terrific, not pathetic, progress. The years whizzed by.

Being forced to imagine not working on this book led me to recognize how stuck, scared, and exhausted I was.A dramatic turning point in the writing of this book came in 2014. By then, I’d already collected four file drawers of manuscript photocopies, microfilm reels, and handwritten archival notes on the Porter sisters. I stored them in a small campus office I’d been given near the library stacks at the University of Missouri, where I was then teaching. One Saturday morning, I heard a report that the library had caught fire overnight, while it was closed. I panicked. I should have been anxious for the fate of its rare materials, but my first thought was selfish: “Oh god! My Porter files!” I told my husband, in all seriousness, “If those files have burned, then I just won’t write this book.” The fire proved to be a bizarre case of arson that caused a lot of damage, but my materials survived.

That day’s shock, as briefly traumatic as it was, opened up a welcome psychological space for me. Being forced to imagine not working on this book led me to recognize how stuck, scared, and exhausted I was. Although people expected me to write it, and investments had been made in me and it, I was out of gas. I didn’t want to admit that the material had defeated me, but I could also feel myself breathing more easily as I contemplated not writing it for a while. The fire showed me that I didn’t have to keep going on as I was. I had no publisher, so I deliberately set the biography aside. I still worked on it here and there, but I largely pivoted away. I took what became a two-year break to publish a different book, on Jane Austen’s afterlife.

Stepping away from the biography was the best thing I could have done. By the time I returned to the Porter sisters, I had not only re-energized. I’d also become a different (and better) writer. I was able to reimagine a different (and better) book. I eventually refocused on the sisters’ topsy-turvy lives, told in their own words, with a greater emphasis on storytelling. I rethought the audience I wanted the book to reach and why. To say that with age came wisdom would be clichéd and untrue, yet that break from the biography cleared the air for me. Even so, it would take five more years to reach the finish line, with further personal dramas and pandemic delays.

Postponing the book’s completion had other unanticipated positive outcomes, including the benefit of new technologies. I’d started writing when most researchers used microfilm machines and some archives allowed in nothing more than pencil and paper. By the late 2010s, many archives began to approve taking personal photographs of unpublished manuscripts. A few materials were newly digitized and even full-text searchable. It transformed what could be known about historical figures and how quickly.

I’m unapologetically proud of having tackled a long, difficult, and perhaps foolishly ambitious book.Twenty years ago, a biographer researching a nineteenth-century person might have traveled thousands of miles to spend long hours scouring unique documents, without no promise of finding needed information. Although there’s still no promise of success (and such trips sometimes remain very necessary), discoveries now may also be made in a matter of minutes in online database searches made from home. By 2019, I found that shadowy minor figures who’d long stumped me could suddenly yielded up firm facts, allowing for the tying up of once-puzzling loose ends in the biography.

I don’t mean to sound an entirely triumphant note. Of course, part of me wishes this biography had taken just five or ten years, start to finish. One drawback I hadn’t considered is that, as I’ve changed a lot as a writer over those years, so have reading audiences changed. All books are written for a future audience that an author can’t know.

But when you write a book that takes decades to complete, you’re writing to potential readers far in the future who will no doubt feel differently about your subject than an earlier set of readers would have. The eager audience that your book may have found decades before might not be there for it when it’s finally ready. Of course, the opposite could also be true. You may have chosen material that resonates even more deeply twenty years on. This sort of authorial risk wasn’t on my mind at all in the early 2000s. I’ll find out soon enough which end of this spectrum my book is on, and that gives me pause.

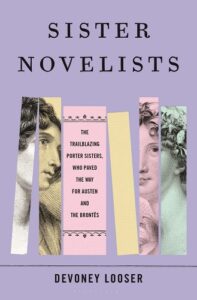

What I can tell you without hesitation is that, with the writing of Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës now behind me, I’m unapologetically proud of having tackled a long, difficult, and perhaps foolishly ambitious book. I suspect I feel about it the same way avid long-distance runners must feel about having trained for and completed a marathon. Not that I would know anything about that personally! In sports, I much prefer speed to distance. But in my author-life, it turns out I’ve managed to acquire some of the qualities of a successful marathoner.

That’s an achievement that ought to strike all of us as a noble, not a piteous, thing in the world of authorship. One problem with it, of course, is that the writer’s form of marathoning involves a race that very few of us will get to run twice. That realization, more than anything, is what makes me determined to hold my head higher and to linger a bit longer at this finish line.

I look forward to congratulating writers who’ve been here before me, and who are here with me now, as well as those who will come after us. We know the sense of satisfaction and rare delights that come with taking the long, circuitous, less-traveled path to publication. But rather than directly invoking Robert Frost, I’d like to offer up instead a line from Jane Austen that I think better captures my present state of mind as a writer. As Pride and Prejudice’s heroine Elizabeth Bennet puts it, “Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.”

_____________________________________

Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës by Devoney Looser is available from Bloomsbury.

https://ift.tt/rGKyARl

2022-10-25 08:54:20Z

CBMiTWh0dHBzOi8vbGl0aHViLmNvbS90aGUtcGFpbnMtYW5kLXBsZWFzdXJlcy1vZi10YWtpbmctZGVjYWRlcy10by13cml0ZS1hLWJvb2sv0gEA

0 Commentaires