On the doorstep of Zwift’s biggest event of the year – the UCI sanctioned Esports World Championship, which is later today – Zwift has managed to get themselves into another cheating and rider ban debacle. This time, for the banning of an individual that published a post of a previously known bug that allowed competitors to change their weight values mid-race without being detected, potentially significantly altering the results of said race. The published post included numerous requests to Zwift to address the issue.

To be super clear: Zwift confirms they did not ban the individual for actually using said cheat, but rather, for publishing it. And like any good drama – the coverup is often far worse than the actual crime. The question is, who was doing the cover-up here? Let’s dive into it.

What Happened:

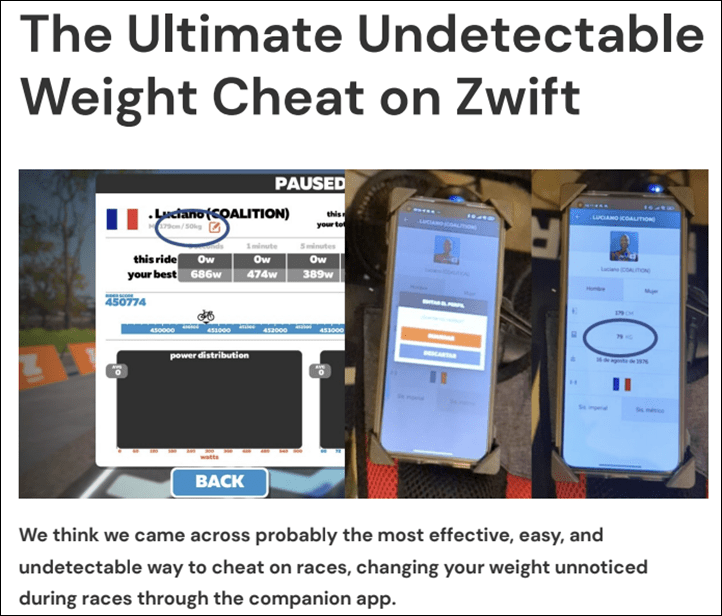

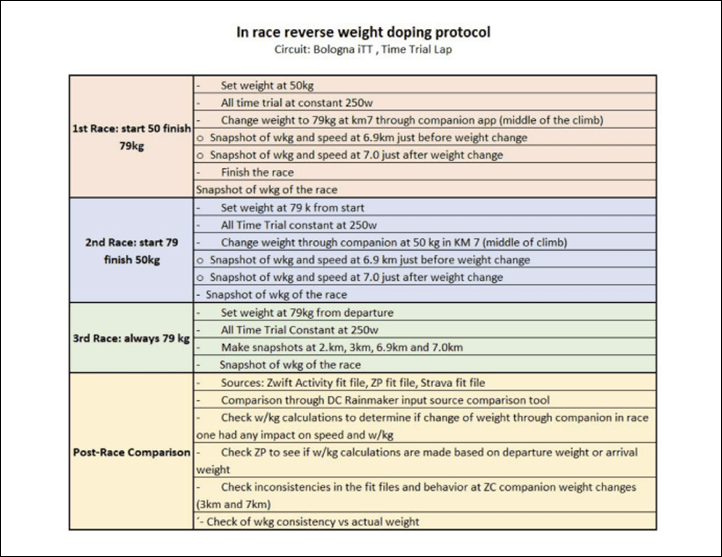

Earlier this past week, Luciano Pollastri published a post titled “The Ultimate Undetectable Weight Cheat on Zwift”, on a burner WordPress (a blog hosting platform), with the publishing designed to draw attention to the bug. The article was then posted to a handful of Zwift Facebook groups.

The article essentially outlined that you could actually change your weight mid-race (such as just after the start), which would immediately take effect (such as before a climb, making you lighter and thus faster in the game). However, the key ingredient was that you could change it again just before the end of the race, and essentially go undetected. The since-removed article outlined in excruciating detail numerous tests of this (in an individual time trial where it didn’t impact other competitors) that the issue was indeed reproducible and real. And also undetectable.

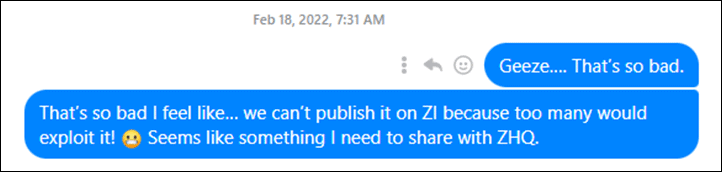

However, it should be noted that the instantiation of a burner WordPress site wasn’t actually the initially planned venue for this post. Instead, it was ZwiftInsider.com (an independent site, but that receives support from Zwift). As outlined by founder Eric Schlange in this post, notes that they didn’t think the bug would actually work. Turns out, it did, and as Eric from ZwiftInsider rightfully pointed out, it would be logical to hold up a moment and ensure Zwift had been notified first, with a chance to respond. The image below from Zwift Insider’s article (text from Eric to Luciano):

However, during that timeframe, after discussing it on a private Discord with a small number of other Zwifters, Luciano became aware that this was previously disclosed on Zwift’s own ZwiftPower forums some two years prior, ultimately without any subsequent fix.

At this juncture, rather than waiting for Zwift Insider to validate with Zwift, Luciano decided to publish the details of the issue publicly. And, while he was at it, gave the post the aforementioned cheating-forward title. The post was shared to a number of very large Zwift Facebook groups including Zwift Racers, Zwift Forum, and Reddit. Some of these groups immediately removed it, since it discussed or promoted cheating. That’s fair, given that such a restriction was a well-known caveat of some of those groups.

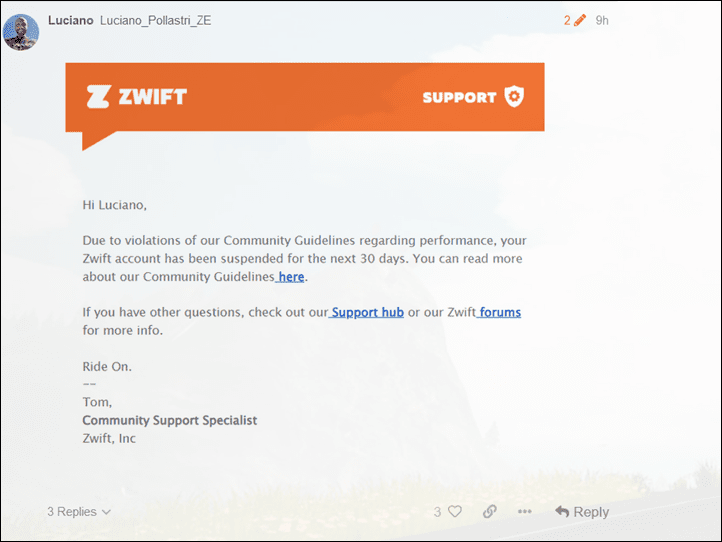

Shortly thereafter, Luciano received a generic notice from Zwift’s Customer Service that he’d been banned, without any context for why.

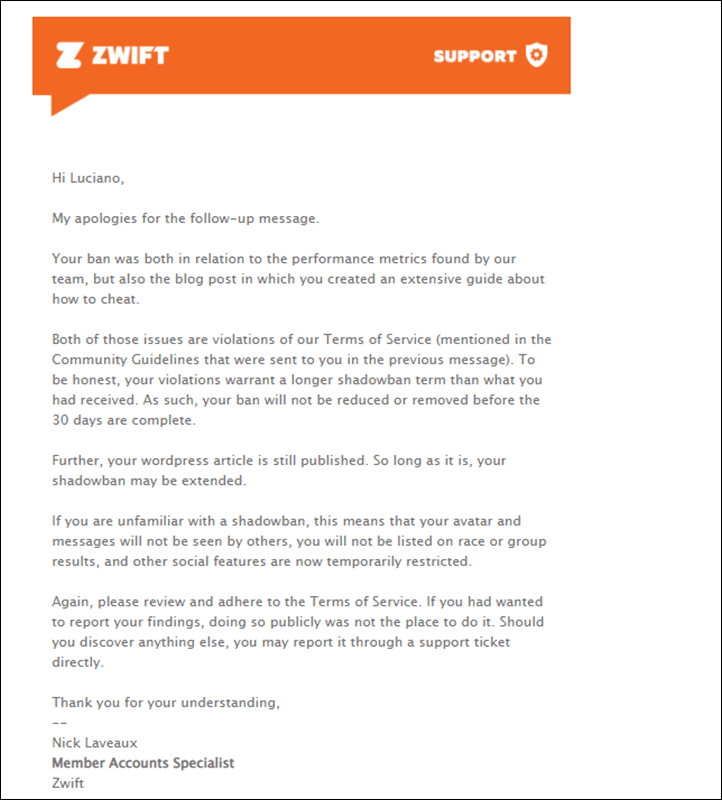

A subsequent follow-up included this slightly more detailed but arguably pretty unprofessional e-mail with further details:

The distinction between ban and shadow ban is basically that the user can continue to use Zwift, but that their results aren’t recognized in races.

In my follow-up conversations with Zwift, the company’s Chris Snook confirmed that Luciano violated their terms of service:

“First, I just want to clarify the ‘ban’. Luciano will have restrictions placed on his account for a period of 30 days. These restrictions will prevent Luciano from showing in group rides, races and will also not show on results. The ban will also restrict him from chatting with other Zwifters during that time. It does not prevent him from using the platform.

He went on to say that specify exactly what was wronged:

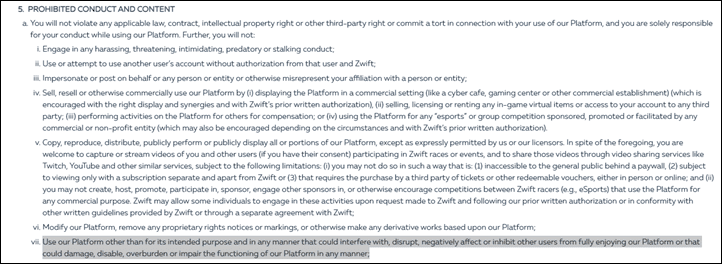

“The reason the ban has been enforced is because his actions have breached Zwift’s terms of service namely, users are forbidden to “Use our Platform other than for its intended purpose and in any manner that could interfere with, disrupt, negatively affect or inhibit other users from fully enjoying our Platform or that could damage, disable, overburden or impair the functioning of our Platform in any manner;”

This is referring to section 5 part VII:

Certainly, it’s within Zwift’s rights to temporarily ban, shadowban, or outright cancel any account for basically any reason. Except, not even the most liberal reading of that terms of service would cover publishing an article on a 3rd party platform outlining an unfixed bug with a plea to fix it, a violation of that line item.

When I pushed back on this to Zwift, it was noted that it was less about publishing the bug, and specifically more about two core things: Publishing it with a clickbaity title, and then sharing it on social media. With Zwift saying:

“Promoting information on how to exploit the platform constitutes a violation of these terms as it can negatively impact the enjoyment of other Zwifters. Luciano has not been banned for highlighting an issue, it is because he chose to host a WordPress site titled ‘The Ultimate Undetectable Weight Cheat on Zwift’ promoting this exploit and shared this on forums and Zwift community groups (some of which also forbid members from sharing information on how to cheat).”

At this point, this starts to feel less like concrete reasoning, and more whataboutism.

But, now’s a good time to back things up momentarily. Assuming that Luciano’s intent was for good (and, I have every reason to believe it was – and I think even Zwift would agree here too), that doesn’t mean the execution was good. Luciano’s choice of titles was at best designed to attract cheaters to cheat, and at worst, designed to raise the profile of such an exploit just days before the biggest event of the year.

For as much #FreeLuciano as one might be, let’s be clear – this title was 100% about cheating – not about fixing cheating. No part of the title, subtitle, or intro suggested Zwift fix it. However, to his credit, if one read past the title area, the third and fourth paragraphs did both ask Zwift to fix it, and suggest how to fix it, saying:

“We believe it is already widely exploited in competition and affects race

results as some indirect conversations occur among riders. In the interest of

fairness of competition, we believe such a simple and definitive way to cheat,

such a substantial hack should be addressed immediately. As most races are

decided on very small variations and in short time periods up to 5 minutes,

this is the simplest and most effective cheat we know so far.Fix seems simple: disable weight change feature through companion app.

Though ZADA seems to have made Zwift aware of the hack, nothing has been

done so far to solve the issue.”

And the article also ends with a plea to fix the cheat:

“Zwift: do something please!!! At least sticky-watters needed to train a little bit

to cheat! This one feels like you left the door of the safe opened!!!”

That does still though ignore Luciano’s rush to publish without waiting for Zwift’s official stance. After all, if this had been in the public for two years, why was there an immediate need to publish this post this very minute – versus waiting a day or two? I don’t know. Certainly, I can understand the publishing desire to get something out and ‘beat the crowd’. But even if I did, I certainly wouldn’t have given it that title. Still, the way the data was presented is super clear that he did his homework on this cheat and the implications it has for Zwift. And ultimately, he repeated multiple times in the article he wanted Zwift to fix it.

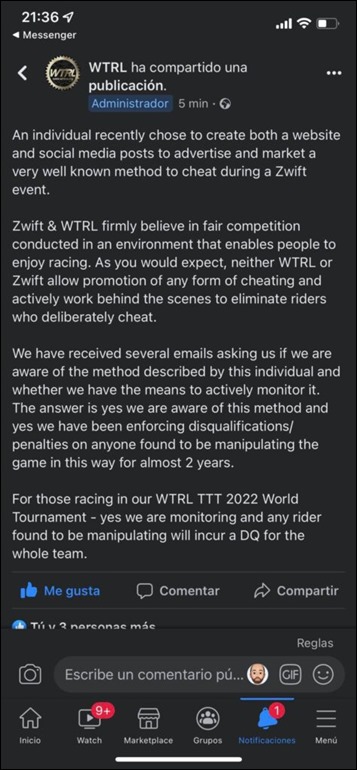

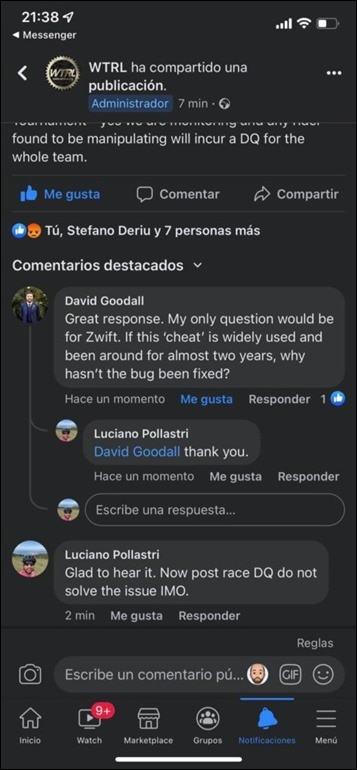

Sliding back into the technical question for a moment, in a since-deleted response from WTRL in their Facebook group, was this message (captured by ZwiftInsider):

As you can see, it implies that WTRL (Zwift’s official race organization partner organization) was aware of this for some two years. A fact that is directly challenged by Zwift themselves. Zwift’s PR lead, Chris Snook, stated in an email that:

“Regarding WTRL’s post, this was issued without consultation with us, so I am not able to provide a comment on this at this time. I am aware of a two-year claim on the cheat. This claim is something that is currently being investigated however, the only known ticket relating to this bug at this time is the one raised a few days ago. The product team is working on a fix now and I’d like us to provide an update on that fix when we are able.””

Of course, in this choose your own adventure plot, you can decide which of the following you want to be true:

A) Zwift knew about it two years ago but never filed the bug or it got closed, or the person responsible moved on

B) WTRL knew about it two years ago but didn’t tell Zwift

C) Zwift never knew about it until this week

Or, some blend of that. There are infinite combinations of the above. In the same way, there are infinite ways to cheat at Zwift. You’re never going to solve them all, though, this does seem like a big and obvious gap. And if WTRL knew about it, why wasn’t it addressed with Zwift (and raised as a priority)? And further, I question WTRL’s claims that they acted upon instances of this being utilized. I’m skeptical that the logging is actually in place for them to do that today.

Finally, the classification of this ‘issue’ this is from a technical standpoint is debate-worthy. Some have called it a “security bug”, others just a “bug”, and others an “issue” (meaning, it can be a bug but not a bug depending on your use case – such as realizing your weight was incorrect). And some further, merely a policy issue. I suppose that’d depend on your perspective. From the UCI standpoint, I could see how this is effectively a security bug – with the security being the awarding of World Championship rainbow jerseys. Inversely, it’s not security in the sense of a potential breach of your confidential information.

However, Zwift lacks any sort of official security/bug bounty type program, or tracking system. Nor any clearly fast-tracked way to submit such a security bug. Perhaps that would have prevented much of the following from occurring. Though, perhaps not. After all, in most responsible security disclosures, the bug reporting person has a set timeline after notifying the company before the disclosure (e.g. 30 days). Certainly, not 0 days (or even negative days), as was the case here.

Going Forward:

It’s easy to pick on Zwift, in the same way, it’s easy to pick on Peloton. Both are large companies that experienced significant growth in a short period, with often a heavier internal focus on sustaining that growth rather than addressing gaps. Both have communities of devoted fans, and yet both have continued to manage to stumble into self-inflicted PR wounds for often unnecessary reasons.

In talking to a bunch of people on both sides of the issue, I get the impression that this situation escalated faster than Zwift realized, and that adults might not have been present ‘in the room’ when the initial ban decision was made. By any logical PR or technical-security standards, there’s no reason this should have ever have made the public’s radar. From a corporate communications standpoint, this should have been handled quietly behind the scenes. Certainly, the adults in the room understood the implications of banning a key ZwiftInsider.com contributor, especially over something ultimately as trivial as pointing out a bug? Zwift has both a very competent external PR agency/team (in my direct experience) that’s well regarded as one of the best in the industry, and they have (also, in my direct experience) a very competent internal PR team. I don’t get the impression either had been this time engaged until it was far too late. Now the situation has escalated to waves of people posting screenshots of them canceling their accounts on Facebook, Reddit, and elsewhere – in support of Luciano.

And from a technical standpoint, certainly, the right public response from any competent engineer would have been “Wow, thanks for pointing this out, we’re gonna escalate this quickly with a temporary fix, and then a longer-term fix”. No matter how frustrating it might have been for said engineers to see the clickbait title that Luciano wrote triggered this avalanche, that doesn’t remove the technical issue that was the true foundation for the avalanche to occur.

Either of those two groups should have prevented this from occurring in the lead-up to Zwift’s biggest event in the last few years. And ultimately, as it stands now, the longer Zwift waits for Mea Culpa, the more media attention this is going to get. And certainly, some of those media are eventually going to ask the next most logical question: “Will you ban my account the next time you don’t like our article title”?

On the bright side, Zwift’s Chris Snook did confirm a fix it on the way and that Zwift themselves is able to detect this specific cheat for this weekends’ UCI World Championships. Further, a fix seems more imminent than previous statements from Zwift that were saying “long term”, with him noting that it’s actively being worked on now, going on to say they’ll provide an update as soon as it’s implemented.

Of course, the problem is – it shouldn’t have taken this giant kerfuffle for that to get a fix for this. It should have simply been just a normal day in a software company. And the fact that it wasn’t is more of an issue than the title of a post.

With that, thanks for reading.

0 Commentaires